Visualising the talk in Singapore's anti-vax communities

Even as Singapore climbs it way to be the most vaccinated country, a number of local anti-vax communities have emerged on messaging platform Telegram. These communities deserve our attention as they are a concern to public health.

Arguably, Telegram packs features that enable the spread of misinformation more effectively than other messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, with the ability to create channels, supergroups, and publishing of various media formats.

On the flip side, Telegram’s features also makes it easier to study these communities. New users are not restricted access to old messages, meaning that the community’s whole history is exposed to anyone. Telegram’s desktop application even allows exporting chat history in machine-readable JSON format.

In this post, I’ll explore how network visualisation can be used to understand anti-vax communities in Singapore. In particular, I’ll look at three SG anti-vax communities that range in age and size.

Introduction

Out of the three communities, two were of similar in age and size, while the third community was the oldest and significantly larger.

| Community | Age | Size |

|---|---|---|

| A | 16th June 2021 | 500 |

| B | 22nd June 2021 | 730 |

| C | 20th April 2021 | 7.6k |

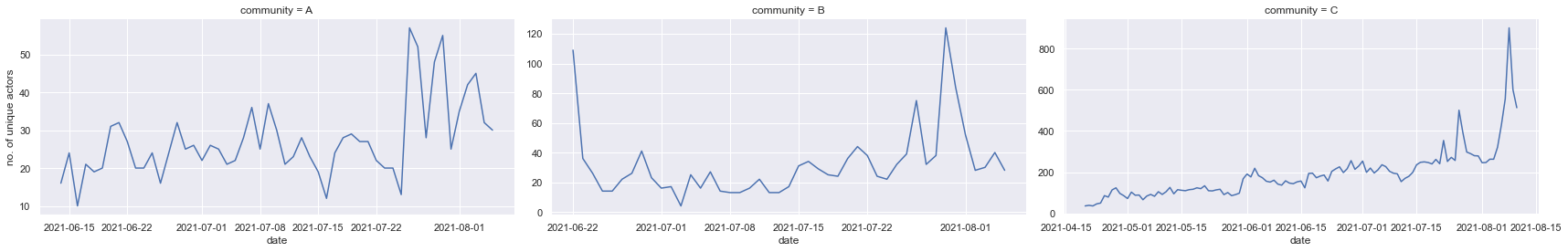

When we plot the activity of unique users over time however, we see positive growth across all three communities.

The Social Network of an Anti-Vax Community

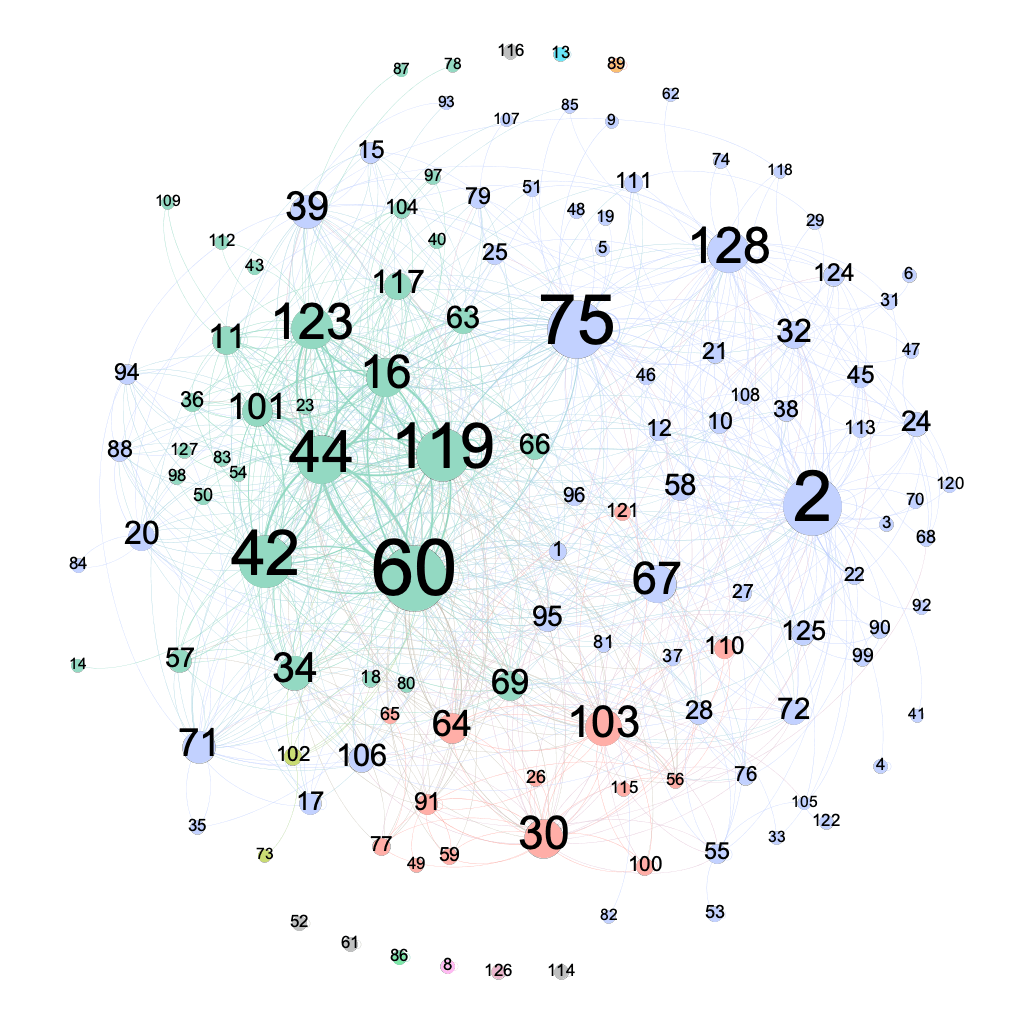

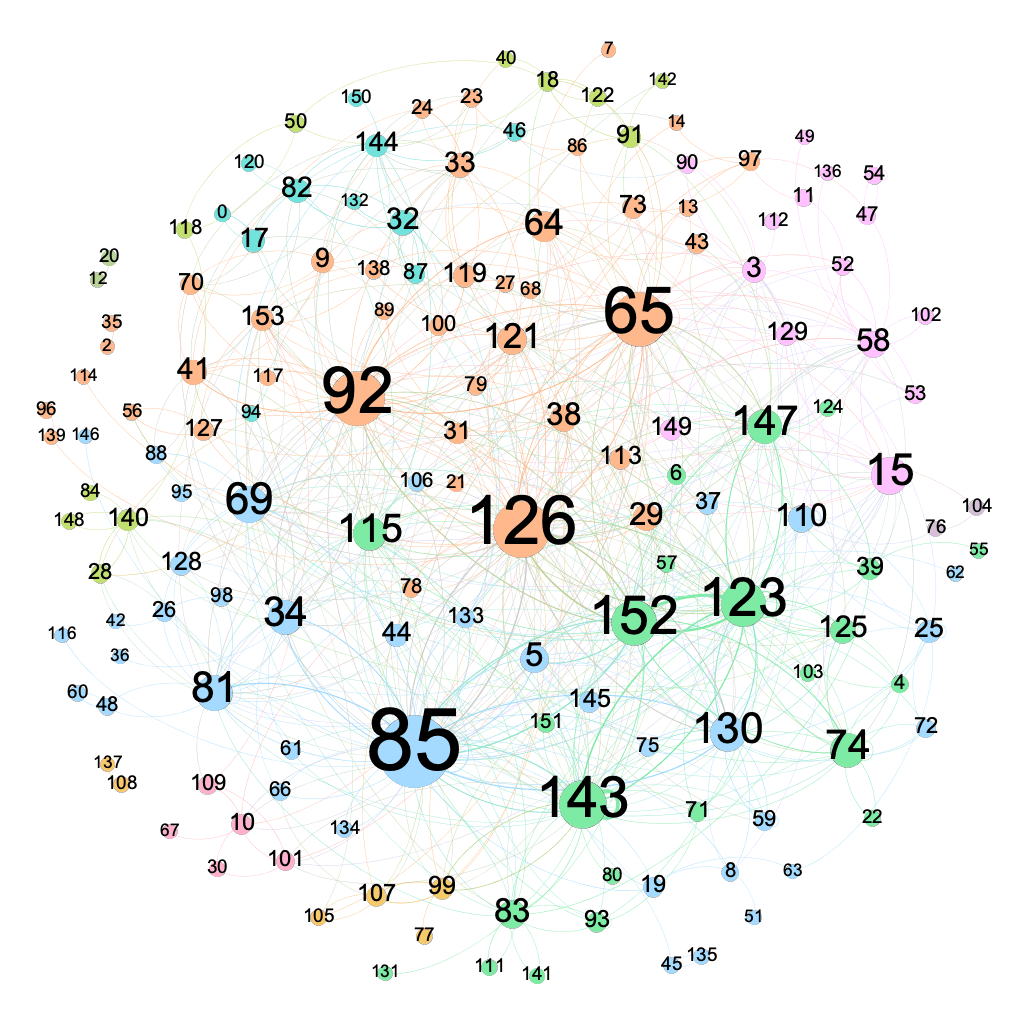

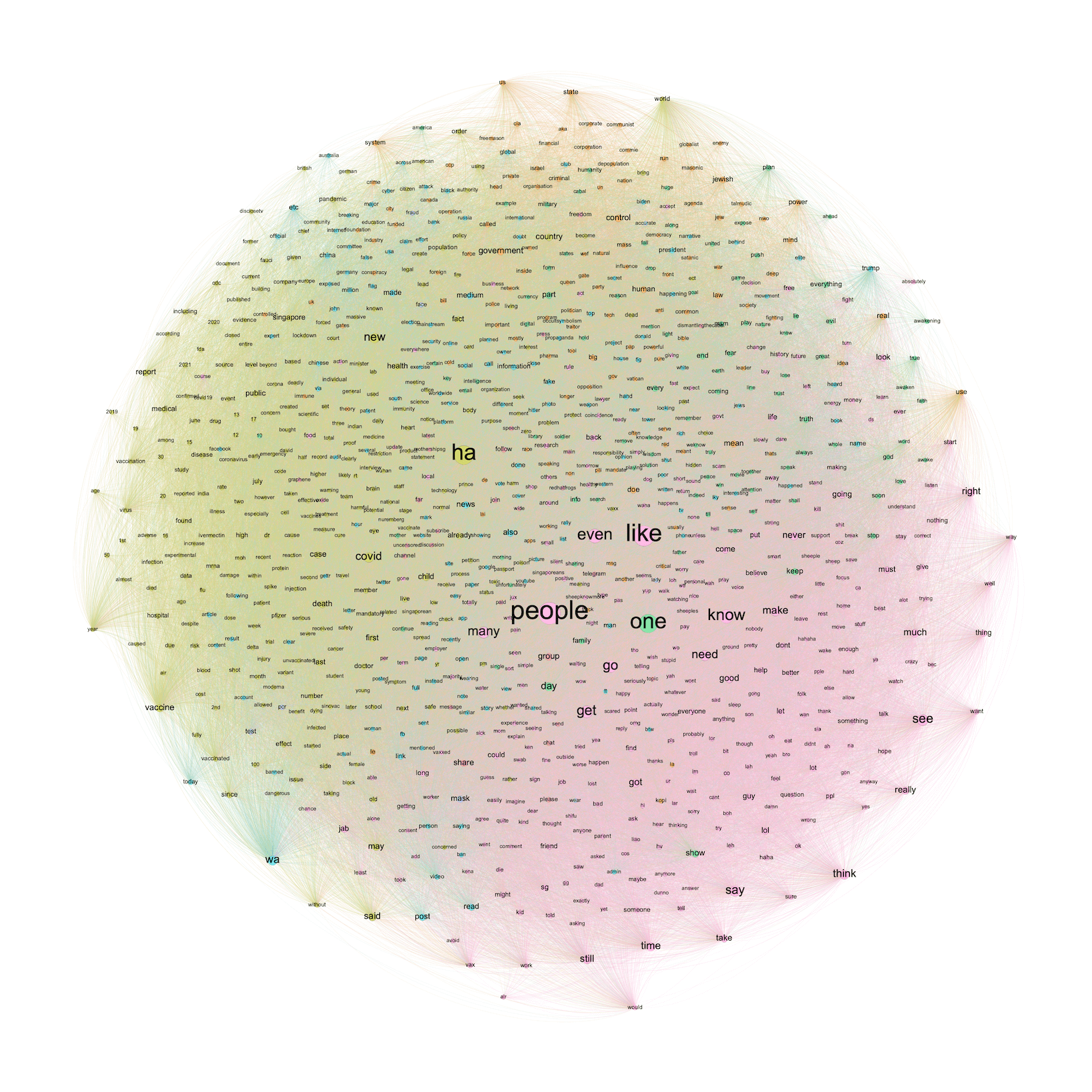

In a social network, each actor in the community is represented by a node. The numbers on each node is a generated id, to maintain anonymity of the data. Each edge represents a user interaction between two actors, which can be a mention, reply, or invitation. The size of the node is proportional to its out-degree, meaning that a larger node interacts with more members in the community. Using modularity clustering, the network has been segmented into community clusters. Open source visualisation software Gephi was used to visualise the network.

The social networks of each of the communities are thus presented.

The social networks of each community are significantly smaller than the actual size of the community as only actors that interact with each other are considered in the construction. That is, lurkers (also called isolates) who do not interact with anyone within the communities have been filtered out.

Within each network, a set of actors can be identified as more active in interacting with other members. Not only are they active in socialising with a more diverse group of members, they also interact with each other more frequently, constituting a broadcast network (e.g. the green cluster in community A), from which most messages are distributed to the rest of the community.

However, as the group grows in size, such as in community C, the number of more-active-than-usual members grow and there are less strong ties present in the network, active members are found interacting across diverse groups within the broader network, instead of coalescing into distinct sub-communities.

Would removing these active users halt misinformation within the group? For a small to medium sized community, this might be effective and sufficient to shut down the community, but for a large community like Community C, it becomes harder to select out the few individuals responsible for the majority spread of misinformation.

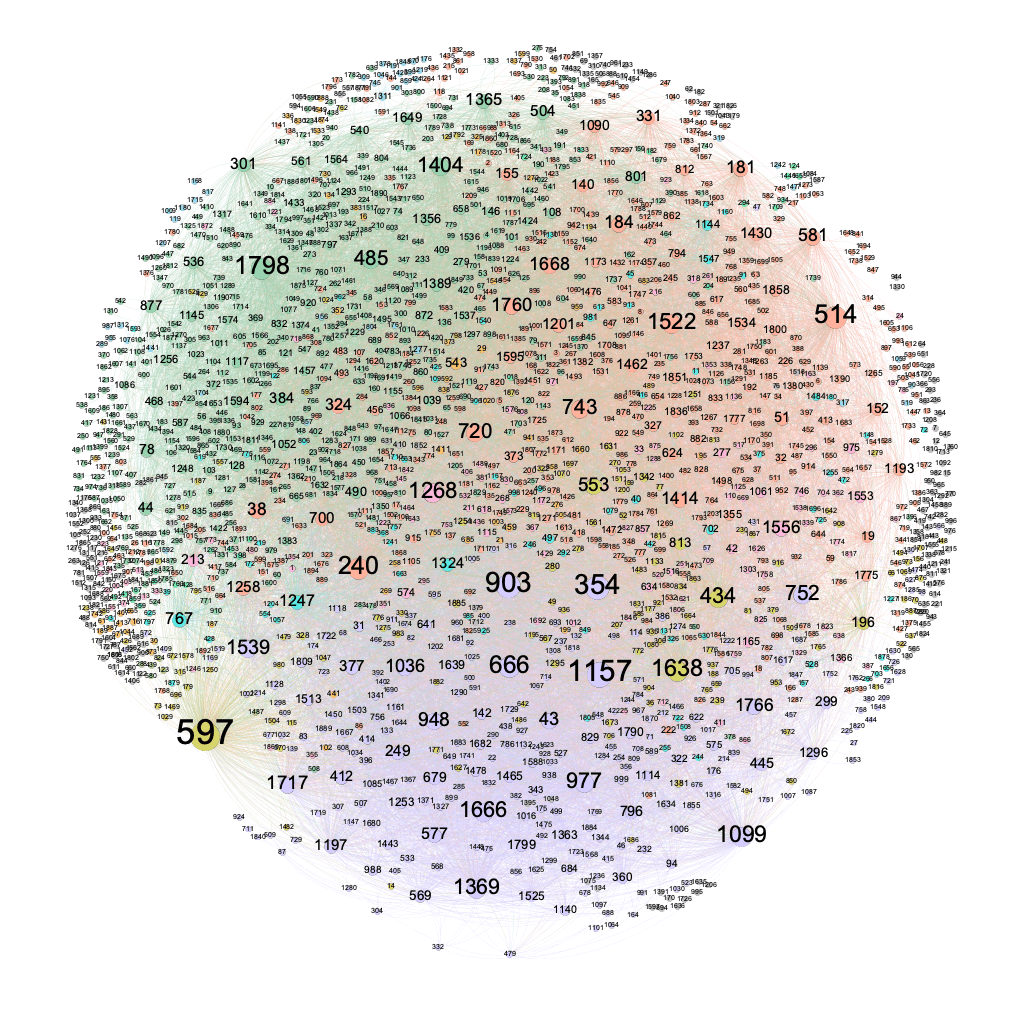

The Word Network of an Anti-Vax Community

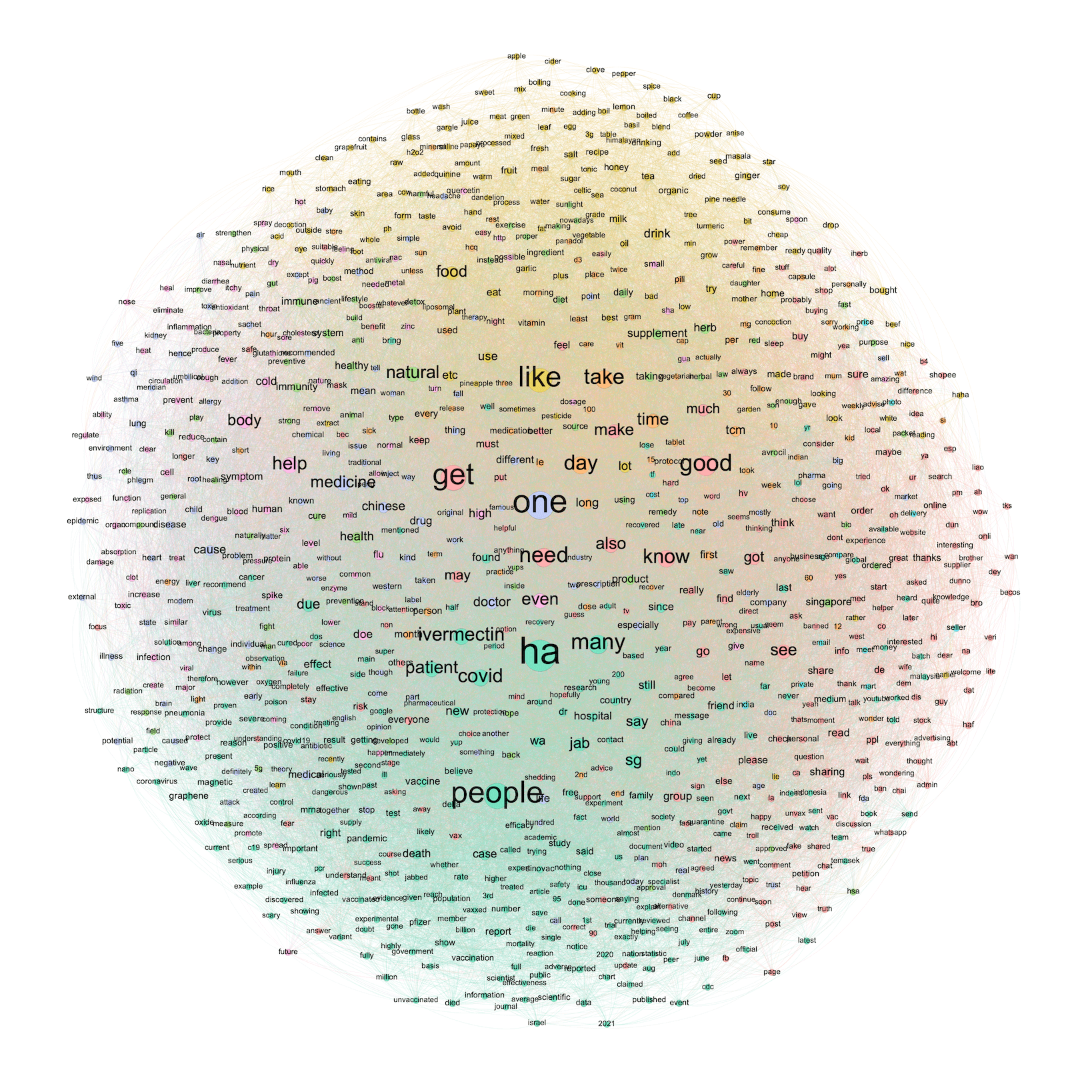

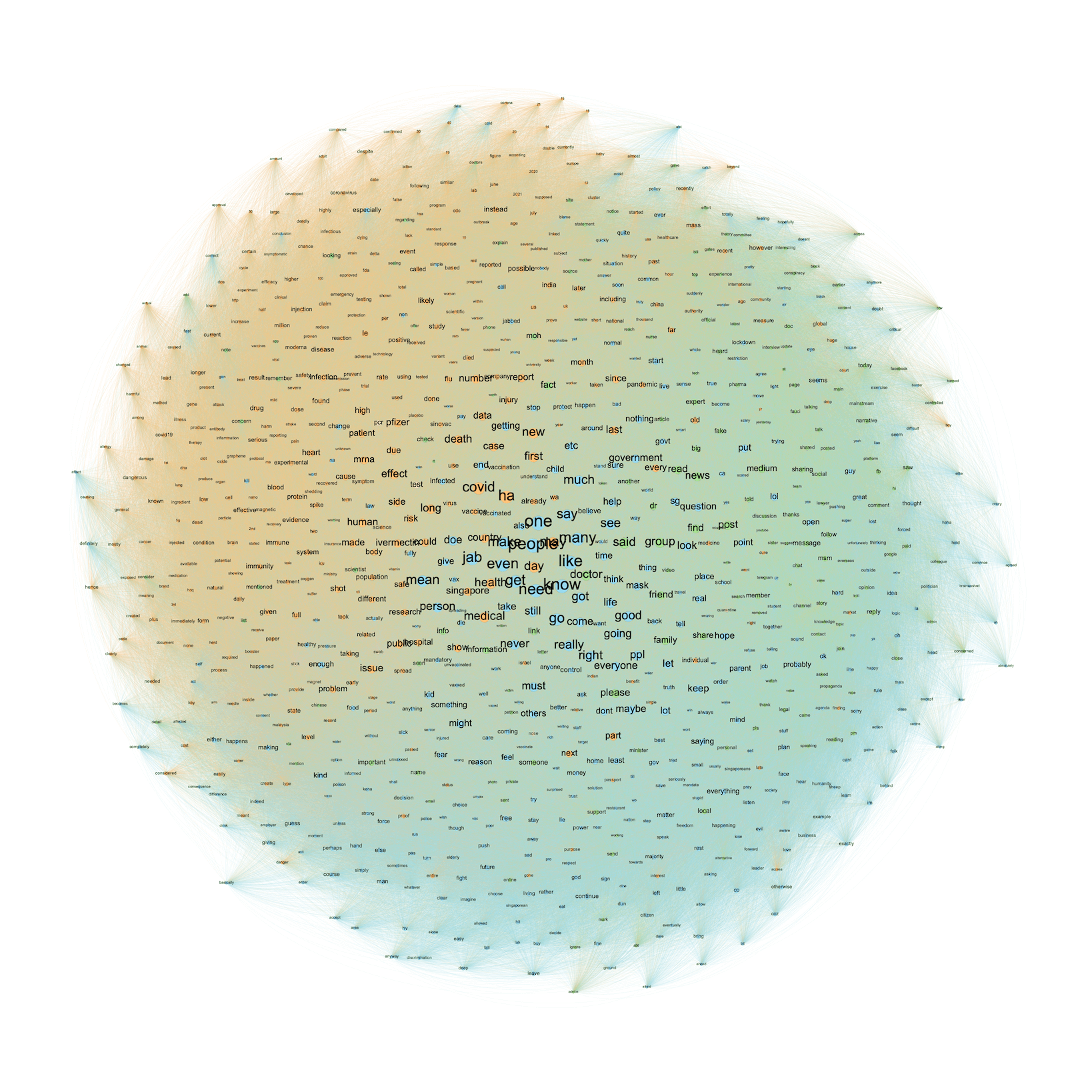

Beyond the social structure of these communities, network visualisation can also provide insight into the conversations that happen within a community, we can use a word co-occurrence network to visualise how words are used in relation to each other in the community. This allows us to identify key topics of conversation, revealing the diversity of topics within the community.

To improve the interpretability of the network, only the top 1000 most frequently occurring word were used in the construction of these networks. The assumption is that the top occurring keywords correlates to the key topics of the community. To reduce the complexity of the network, words were lemmatised using the NLTK toolkit. Stopwords were removed as well.

Within community A, three clusters can be observed, though it appears no particular keyword anchors the conversation of the community. The green cluster pertains to medical information such as information on vaccines and the covid virus. A pink cluster reveals community actions, including asking for advice, personal opinions, and informal requests. A third cluster in blue pertains to the news and media, a staple source of information for these communities.

Community B exhibits more visibly distinct clustering. A green cluster pertains to information on vaccines and the pandemic, such as death counts, vaccination reports, and case updates. The yellow cluster is particularly unique to this community, pertaining to alternative medicine and home remedies, evidenced by the names of organic ingredients and household chemicals. The pink cluster, on the other hand, relates to symptoms and negative reactions from vaccines. It becomes clear that community B has a specific interest in alternative remedies and distrust and anxiety over side-effects and potential harm from the vaccine.

Finally, in community C, clusters are the least distinct, indicating a mixing of various topics in conversation. This is perhaps a consequence of the size of the community, which results in more diverse conversations. However, an cursory look at the words that make up the network reveals that community C exhibits similar topic clusters as community A.

Generally, within anti-vax communities in Singapore, members use reports on negative symptoms to view vaccines in negative light. Vaccines are often mentioned together with words such as toxic, risks, and experimental. How vaccines might negatively affect the body is a topic also discussed in detail, with specific references to organs in the body such as the liver or heart, as well as specific symptoms such as fever and stroke. In response, alternative treatments are frequently discussed, and community B is particularly unique in its focus on home-based natural remedies.

Finally, we can also observe evidence that these community channels are actively promoting and encouraging the spread of misinformation. These take the form of frequent requests for more information, as well as encouragement to share misinformation, specifically targeting friends and families.

What can we do?

Recently, these communities have been exposed to our mainjournal media and social networks. People have been joining these communities either to satisfy their curiosity or to troll. However, this does little to resolve the problem as such communities can quickly migrate and start new community channels, like the mythical hydra. Should the government be given the power to shut down these communities in a similar vein to POFMA? Or perhaps we should seek to understand these communities and learn to speak their lingo, in order to change their opinions using the power of their own words.